Related Work

The human-computer interaction community has long been working together to tackle the problem of digital photograph storage and sharing, though few interfaces have focused specifically on narrative-creation for sharing. In addition, researchers in sociology, anthropology, visual studies, and cultural studies have explored personal photography and narrative creation (especially for prints in albums), many elaborating on the ways in which it contributes to identity creation, communication, or other social actions. In this section, we will first discuss the research on photography that has been done in human-computer interaction, particularly the research on photo-sharing applications and timeline applications. We will also discuss several popular online photo-sharing methods for purposes of illustration. Finally, we will summarize the research in social science that relates to photo-sharing and narratives.Digital Photography

Many tools exist to help people organize and retrieve their digital photographs, though few explicitly help in sharing and only one explicitly supports the creation of narratives for sharing purposes. Bederson’s PhotoMesa interface provides a unique photo visualization using quantum treemap organization and “focus+context” interaction (Figure 2a) [6]. PhotoTOC [20] and Timequilt (Figure 2b) [17] use representative thumbnails to provide an overview of pictures and organize them by date. Harada et al. also provide a timeline interface and an event-based interface for interacting with photos on PDAs [15]. Photofinder (Figure 2c) enables annotation of parts of a picture for searching and “storytelling” purposes. MediaBrowser (Figure 2d) integrates many of the above ideas and provides many views, including a time-based view, and many interaction mechanisms, including a two-level fisheye and easy selection by group or keywords [10]. Fotofile (Figure 2e) incorporates narrative-making, as well as bulk annotation, a hyperbolic tree view, and some automatic feature extraction, into a digital album-making system, but for the purposes of archiving rather than sharing [18].

Some tools exist to assist in the creation of narratives. CounterPoint is a zooming presentation tool that allows users to define multiple narratives through slide-based presentations [14]. Balabanovic et al. created a tool explicitly for narratives and sharing digital photos (Figure 2f) [5]. Audio can be recorded over a photostream to create a multimedia narrative. These images and audio files can be sent to distant others, though the interface is best with copresent others (particularly because recording audio without an audience synchronously listening is awkward and reviewing audio is cumbersome). Picasa [4] and other commercial photograph organizers also provide some of this functionality. Picasa in particular gives a timeline view of all photos, similar to the preliminary sketch of our interface above (see Figure 3a).

Several of these interfaces – particularly the tool developed by Balabanovic et al – address the issues of narrative formation and photo-sharing. The PhotoArc interface is unique, however, in providing an intuitive timeline view of the narrative, enabling the creation and viewing of multiple overlapping narratives, focusing on photo-sharing, and allowing flexibility in narration and response. The other photo-organization techniques summarized here could provide a framework for navigating among photographs in the PhotoArc system that are not currently on PhotoArcs.

Figure 2. a) PhotoMesa, b) TimeQuilt, c) PhotoFinder, d) MediaBrowser, e) Fotofile,

f) Balabanovic et al’s photo-narratives interface

Timeline Interfaces

As mentioned above, Picasa provides a photograph timeline view in its interface (Figure 3a), and many photo systems organize photographs chronologically. Flickr’s “Organizr” interface provides a clickable summary timeline with sliders along the bottom of the screen (Figure 3d). Closer to home, the MMM2 developers created a timeline view of MMM2 photographs to use in photo-elicitation interviews with MMM2 users last summer [21]. Beyond the photographic realm, the filesystem Lifestreams is built on a chronological storage and retrieval model [11], and now Nokia provides a similar system in its LifeBlog software (Figure 3c), which automatically captures SMS and cameraphone pictures and organizes them chronologically.

Because most people organize their photographs chronologically and because photographic storytelling progresses in a linear fashion – even though the course of progression may change from one telling to another – we chose to use the timeline metaphor for our PhotoArcs interface.

Figure 3. Examples of timeline interfaces: a) Picasa, b) MMM2, c) LifeBlog, d) Flickr

Photo-Sharing Media in Use

Many sites are dedicated to photo-hosting and photo-sharing. We will not attempt to be exhaustive in our descriptions since the number of photo-sharing sites and applications is very large. Instead, we will discuss two particular examples – Flickr [3] and narrative photoblogs – that are similar to many of the others and also call attention to who of the most common modes of online photo-presentation, one with a focus on photos and the other with a focus on stories.

Flickr and other sites geared specifically to photo-sharing allow the user to upload and annotate individual photos, to sort them into sets, and to annotate the sets themselves. However, users generally cannot create a narrative unit out of a set of photos that can be viewed all on one page. For example, consider a series of photos on Flickr titled “The Adventures of Bat Barbie” (Figure 4). Each photo has a description of what the fictitious character is doing, but there is no mechanism for encouraging users to tell a story from one photograph to another, and no way for viewers to get an overview of this narrative.

Figure 4. An online photo-narrative that could benefit from PhotoArcs: “The Adventures of Bat Barbie” (http://www.flickr.com/photos/lemonhound/sets/1372462/)

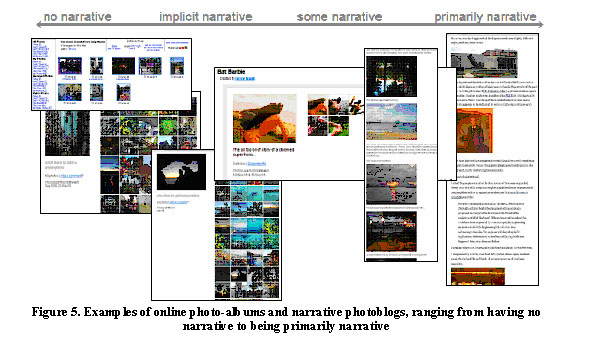

Many tech-savvy photo-sharers are getting around the limitations of online photo-sharing sites by creating photoblogs. While some photoblogs consist entirely of photographs that have no narrative or an implicit narrative told through the sequence and subject matter of the photographs themselves, others combine the narrative potential of blogging with photo-sharing to create rich online photo-narratives (Figure 5). Narrative photoblogs in particular are the most similar to the interface we are proposing, and such narratives could potentially be automatically converted into PhotoArcs. However, the general model for blogging is that there is only one author for a particular narrative, comments appear at the bottom rather than interspersed throughout the narrative as they would be in face-to-face sharing, and most bloggers don’t alter their original story based on the comments they receive. The PhotoArcs system is intended to be easier to use and to enable a higher degree of interactivity between the storyteller and the listeners (or co-storytellers).

Research in the Social Sciences on Photographs and Narratives

In addition to this work in HCI, research in areas such as sociology, anthropology, visual studies, and cultural studies address photography and photo-sharing as a social activity. Chalfen [8] and Musello [19] both conducted ethnographies of family photography, focusing on interviews and family albums. Chalfen found that “snapshots” served three roles: artifacts of social communication, vehicles for constructing memories, and signs of cultural membership (by establishing and reinforcing what is considered “photo-worthy”). Musello found that the narratives created around family photographs and photo-albums played an important role in a family’s ongoing narrative and its group identity. Both Chalfen and Musello found that people shared pictures face-to-face, through albums or slideshows. In corroboration, Bruner [7] discusses the role of narratives in identity formation, reinforcement, and performance:

Even our own homely accounts of happenings in our own lives are eventually converted into more or less coherent autobiographies centered around a Self acting more or less purposefully in a social world. Families similarly create a corpus of connected and shared tales … Institutions, too … ‘invent’ traditions out of previously ordinary happenings and then endow them with privileged status.In 1995, just as digital photography adoption started to take off, cultural theorist Don Slater predicted more communicative uses of images and expressed a “utopian hope” that in the future people would be able to tell their own stories photographically [1]. In our recent research, we found that cameraphones connected to internet-based sharing led to exactly these outcomes, as people sent one another images as messages and posted them online [21]. The most common audience for photo-sharing is others who were at the same event or those that “should have been there” (as one interviewee stated) – people who know those who were at the event and have an interest in finding out the details of what happened. Another common audience is distant family and friends who may not have as much invested in learning all about a particular event as just “keeping tabs” on each other through more general stories and images. Finally, some present their photographs to strangers.

Despite this rise in internet-based sharing, we have found that people value prints more than digital photos and prefer an element of human interaction and feedback in their photo-sharing – the best being face-to-face, but also over the phone or through email or instant messaging [23]. As more people adopt digital cameras and start wanting to share photographs with distant friends and family, the need for easy-to-use photo-narrative tools such as PhotoArcs that combine the advantages of face-to-face sharing and online dissemination becomes ever-greater.